Last edition I talked about a Phd as an open-ended (almost spiritual) journey. I also talked about why it is that the Phd has come to fill this particular social function, and whether or not this comes at the exclusion of other forms of knowledge creation. If, having read that, you still think a Phd and the type of knowledge that it produces is for you, then this edition will hopefully provide some practical advice about how to go through this strange process. As with the last one, I hope to keep these observations broad enough that even if a Phd sounds like your idea of hell, you can still get something from it.

1) You Probably Won’t be a Professor

I met someone at a lunch recently. Let’s call him Joe (not his real name).

Someone introduced us and told him that I was finishing my phd. His eyes lit up. “I’m going to do a Phd!” That’s great I said, what are you going to study? He paused for a moment and said, “yeah I just decided in the last lockdown that I want to be a professor. So I’m going to do a Phd!”

Hate to break it to you Joe…

One of the saddest but most profound comments I have seen recently was from an academic on Twitter who said that when planning your career as an academic you should not look at any of the academics who have come before you. I can’t find the exact tweet but it was something along the lines of; “They are like stars. Just as it takes centuries for the light to reach you so that what you are seeing is actually a reflection of the past, so too are the academics in your department carrying information that is now irrelevant to your career.”

You should not go into a Phd if you want to be a professor because almost none of us will make it there. There are simply way too many graduates and not enough jobs. It is very easy to end up trapped in a precarious cycle of short-term contracts, bouncing around departments and countries and never getting anywhere near a stable career (or a family, or any of the other trappings of the normative good life like a house). That’s even if you’re lucky enough to get those contracts, which are each fiercely and intensely fought for. The same dynamics that exist in the economy at large––extreme inequality compounded by the visible success through social media of a vanishingly small group of people––are reflected in the academy today.

Assume I want to stay at Oxford. The next and most prestigious step (arguably) is to become a Junior Research Fellow (JRF). This is a four year post with minimal teaching requirements that gives you the space to write and think and hopefully produce truly original work. Literally hundreds of people apply for each of these posts. They are also clustered around various disciplines. So not only would I be competing against the best anthropologists/China scholars, I’d also be competing against the best historians, sociologists and economists. How a department is supposed to evaluate who the “best” researcher is between someone who studies mental health in China from an anthropological perspective vs. an Economist who works on post-conflict development in Colombia is beyond me. This means it’s a lottery, and should be understood as such. You might be the best person in your field, but they had someone ten years ago do a project that was somewhat similar to yours and thus decide against you. Who knows. The process is entirely opaque from the outside.

Imagine you do get the JRF, you then have four years to prove yourself worthy for a stable faculty position. You’ll have to publish that book! And journal articles. Host a few conferences. Create a network of scholars on your topic. Do media outreach. Teach classes. Do admin work for your department. Do unpaid work for a journal (or a few) etc etc. All this, and a JRF pays less than £30,000p/a (they do offer housing, normally in a college, but this does mean you’ll probably be 30y/o at least and living in a glorified student dorm)1. Oxford was, until Winchester beat it this year, the least affordable city in the UK, to put that figure in context. If you do get through all of that, you then need to get tenure, which is its own trauma. You’ll have to remain relevant within your field for literally decades, create genuinely pathbreaking work, and even then you might be caught up in the politics of the department (or the country at large; see Nikole Hannah-Jones’ tenure rejection at UNC).

All this to say, don’t go into this because you want to be a professor. The sad reality is that you probably won’t be one. The same is true of many industries. In a previous post of this newsletter I noted that America lost 26,000 journalism jobs in the previous decade at the same time that 500,000 people graduated from journalism school2.

If you are under the age of 30, take career advice from anyone over the age of 35 with a pinch of salt (or not at all) because their world is simply not the same as ours. The dynamics of precarity, spiralling inequality, the hard-to-parse effects of technology and the impact of unstable politics/climate (e.g. pandemics!) mean they are speaking to you, literally, from a different planet.

This is incredibly depressing and I wish I had a better answer. Some people do make it to be professors (I guess?). Also as a friend recently said to me, in the context of working in a kitchen, chefs are not restaurant workers. There are plenty of ways to be a chef today that don’t involve the grind of endless double shifts (look at the rise of the youtube cook, or online recipe developers). Similarly, academics are not university professionals. Writers are not newspaper professionals. There will be many ways to express your talents and knowledge elsewhere, so the endeavour is not for nothing. But you do have to steel yourself to create a value system that is not tied into the trappings of success that are legible to generations above you. This ties into my next point:

2) Goals vs. Purpose

We have to separate between having a goal and having a purpose. Wanting to be a professor is a goal, it is not a purpose. Imagine you succeed. You get to be a professor one day! Now what?! You have to profess, daily, for the rest of your career. Does that appeal to you? Once you achieve your goal, what is supposed to sustain you? Andrei Agassi was the most depressed when he was the world’s greatest tennis player. Why? He actually hated playing tennis and only did so to please his tyrannical father. Once he was the top player in the world he had nothing to strive for anymore. He’d powered himself right to the upper limit and now there was nothing left but to hold his place there. It was agony. He ended up taking crystal meth.

That’s an extreme example, but I think it hits at something very important. Agassi had a goal (it wasn’t even his, it was his father’s), which was to be the number 1 tennis player in the world. But achieving that goal will break you if you can’t hack the banal reality of playing tennis everyday. The same is true for academia. If your goal is just to get a Phd (or become a professor) either you’ll get it one day and be left completely hollow by the aching void of what’s next or you’ll be tortured everyday on the way there because of the quotidian reality of what you’ll be doing. What you should be aiming for is to cultivate a way of being in the world and a set of questions (and ways of trying to answer them) that will guide you for the rest of your life3. Ideally, the Phd is just a stage you pass through, a largely meaningless piece of paper and some letters after your name.

3) Choosing a topic

One of the most bizarre and difficult aspects to explain about a phd is how you start off with a topic that seems to be wildly vast and somehow manage to produce 300 pages on something so narrow. That is academic knowledge production today. Everyone pushes their tiny niche forward, in the hopes that each of these micro-efforts expands the knowledge base. The kind of grand, unsubstantiated, messy ‘Big Idea’ thinking of previous centuries is not how knowledge production works today. You could find hundreds of scholars around the world debating specific aspects of Hobbes’ concept of the Leviathan or disproving from a meta-physical level using fMri scans Descartes’ mind/body dualism, but it would be basically impossible to be taken seriously as an academic today if you tried to do something as sweepingly general as the original texts people are working off.

That’s not a complaint4. But it’s worth keeping in mind because, as I said in the last newsletter, you might start out with some lofty aims and end up with something hilariously small. Your research will also draw you into questions you never thought about asking before you started5. All this to say, prepare for your project to look nothing like what you intended it to at the start.

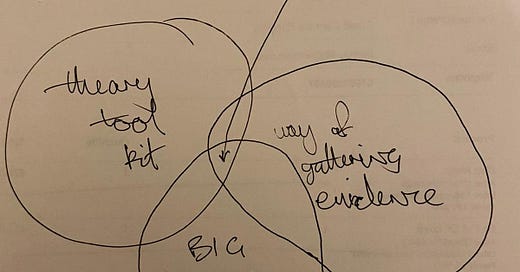

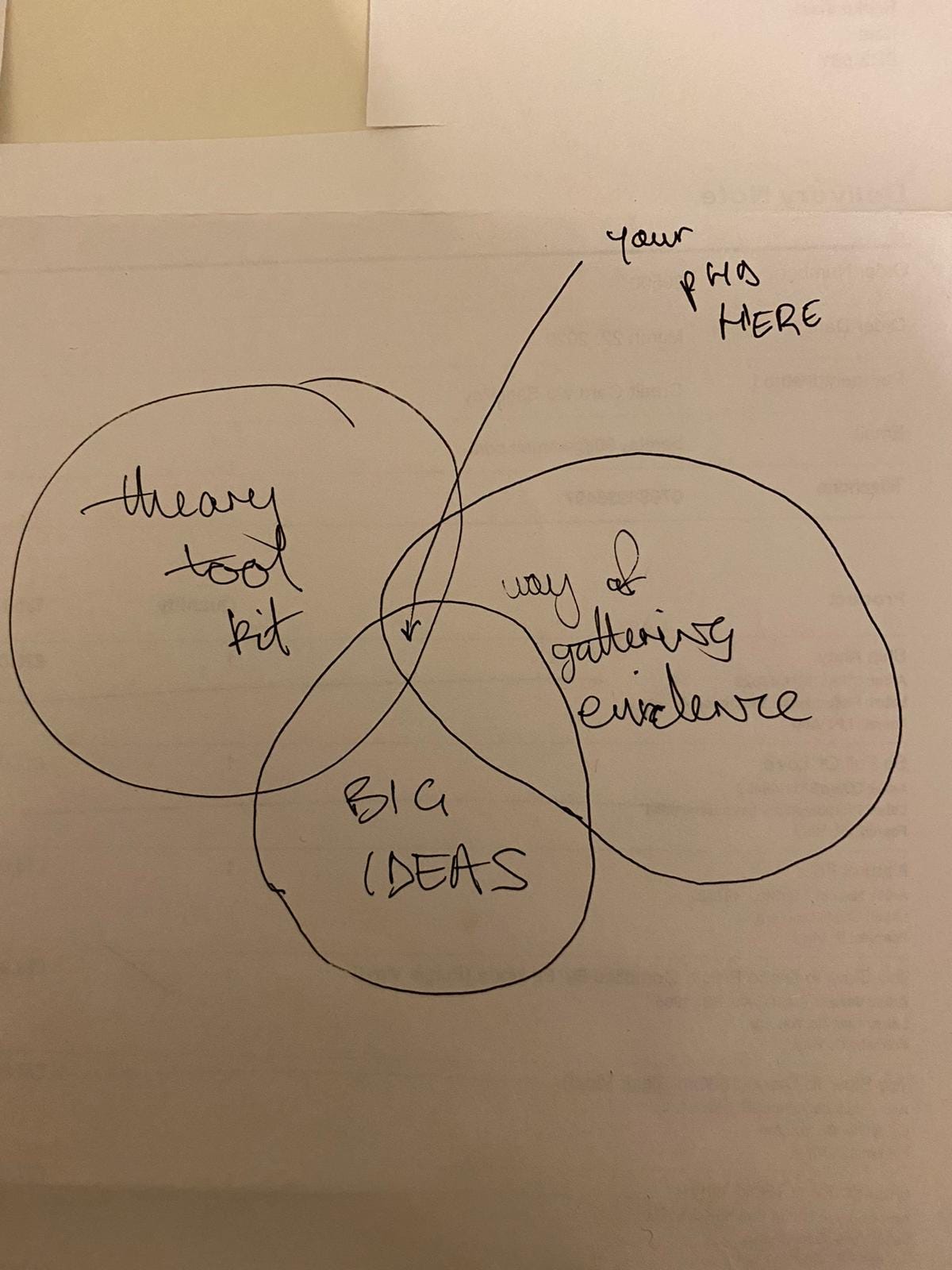

Enter Barclay’s Venn Diagram of Phd success!

I didn’t have this four years ago and I wish I had. Considering that a Phd may well not land you a job in the end, you need to make sure that it is going to provide you with some transportable tools and life experiences.

a) theoretical toolkit. what do you want to be very fluent in? is it how to do statistical modelling? is it how to theorise power (hey Foucault!)? is it how to do ethnographic research? is it how to map space time? This is probably the thing you’ll end up carrying the most after your phd, so make sure you are developing a toolkit you’ll actually want to use again!

b) way of collecting evidence. who are you interviewing? who are you reading? will your research let you travel? if so, where? these are important questions and I think it’s completely valid to choose a Phd in part based on the fact it will allow you to meet or work with a community of people who inspire you/interest you or take you to a place you’ve always dreamed of engaging with deeper. I loved living in Chengdu for my fieldwork. I’ll never regret that choice.

I have a really close friend from highschool who is now studying a Phd on the far-right and how they weaponize misogyny. It’s incredibly important work (here she is as an expert interviewed by the Guardian after the Plymouth shooting). I truly admire her for doing what she does. It’s incredibly dark though and she spends time in corners of the internet that I would find deeply troubling. She has the strength to do that, but I do not. Be intentional and understand where you are willing to go for your research (both physically and mentally).

c) big ideas. Even if you won’t end up coming out with a broad and unsubstantiated generalization of the world, you can choose a Big Idea you want to really grapple with. This may well be the question that becomes the purpose of your life. For me it’s mental health. There are personal reasons for this. But it’s also a topic that is broad enough to encapsulate many other things. My project is on psychological counselling in China, but I’ve written about mindfulness technology (I wore a meditation headset for a whole summer) and I’m now working on a piece about Ai therapists. I’ve read books on health, inequality, suffering, technology, subjectivity, neuroscience, psychology, mushrooms, and drawn from studies from places as diverse as Galen’s Rome to aruyvedic practice in contemporary India. Whatever your Big Idea, make sure it’s one that will let you read as broadly as possible.

4) Supervisor relationship

You manage to find a topic that really moves you. You get into the university of your dreams. You are ready to become a great thinker! This is the biggest thing that’s ever happened to you!

For your supervisor on the other-hand, you are one of maybe 8 phd students they currently have. Maybe they also currently have a coterie of masters students they are shepherding through their own dissertations. They’re running undergrad courses. They have their own research to attend to. They have office politics they’re navigating. Then they probably have a family. If you have a late-career academic, you might be 30th phd student they have had.

It’s necessary to remember this, because it represents the crushing imbalance you might feel between the importance you place on your project (and that it has to your life) and the amount of help that your supervisors are actually in a position to offer you.

In the Uk you are highly dependent on your supervisor. It’s usually only one, but increasingly they are trying to increase to two to make the dynamic slightly less intense (my funding required that I have two supervisors, which I’m very grateful for). One friend was ghosted by her supervisor for nearly half a year. The supervisor was implicated in an academic scandal that engulfed her college. If you only have a single supervisor, then something like that happening can be devastating. For my friend it was extremely damaging to her mental health as her sense that her work had any meaning nosedived. What happened had nothing to do with the quality of her work or her value as an academic, but it’s hard to feel that that is true when the person supposedly in charge of your academic future suddenly vanishes on you.

This applies in other careers. If you have a mentor, remember that there is a clear imbalance in what you are hoping they can offer vs. what they can actually show up with given all the other commitments they have in their lives. And if you are a mentor, remember that for you this is just one person with a dream, but for the dreamer this might be everything. Hold that with the gravity it deserves.

5) Funding

My personal opinion is that it is unethical for a university to offer unfunded Phd places. I do not believe that under the current system of mentorship, the lack of academic job opportunities post-graduation and the fact that you are contributing to the knowledge-base, prestige and future of your department/discipline that anyone should be expected to pay a significant sum of money to do a phd6.

I know this is a controversial opinion. I know I’m speaking from a position of immense privilege as someone who does have full funding at a top university. But given what I have seen, I could never recommend someone in good conscience to do an unfunded PhD7. It’s too much stress to add the financial burden on top of the quotidian existential stress of trying to complete something so abstract and personal (see the previous edition of this newsletter).

Even with full funding I can’t pay my rent now that I’m living in London. On top of my PhD I work 30h a week as a chef in a restaurant (which counts as part time because that’s the nature of restaurants). The last few months because of the hiring crisis and chefs constantly being out with covid or self isolating has been incredibly tough. My academic work has really suffered. I can’t imagine if this had been for the majority of my PhD. I can only do this because I didn’t work in a kitchen during my fieldwork or during the height of the pandemic which means the majority of my reading/thinking was already done. If I didn’t have funding then 30h a week wouldn’t be enough. That’s the reality of many students who have to make incredible sacrifices to try and complete their PhD. And as we know, the job prospects aren’t great after. How are you supposed to compete on the academic job market after a PhD you self-funded when some of your competitors had 4 years of complete freedom to do their research, publish and get paid to fly to network at conferences?8

Let’s be real with some numbers. An MFA is the equivalent of a PhD in that it is a terminal degree in arts. At Colombia university, students of the MFA in film typically leave with had a median debt of $181,000.

Yet two years after earning their master’s degrees, half of the borrowers were making less than $30,000 a year.

To put this in perspective, Columbia’s annual budget runs about $5 billion. They are building a 17-acre campus expansion in upper Manhattan that broke ground in 2008. Their priority is clearly not to their students: it’s to the donors who want their names on a fancy building. Former students describe themselves as “financially hobbled for life.”

There is an argument that expanding loans expands access to PhD programmes. There is evidence for this. In the UK after the postgrad loan was introduced by the government enrolment on loan-eligible master’s courses “increased by 74% among black students, and by 59% among those from low undergrad participation areas – a proxy for disadvantage – between 2015/16 and 2016/17. Both groups had previously cited finance as a major barrier to a postgrad degree.”

But while this sounds good in theory, the reality is that increasing the debt burden for marginalised groups does not benefit them in the long run. Longitudinal studies have shown that for Black graduates with high debt burdens from attending university in the US (where this practice has a longer historical record to draw on) the debt cancelled out the gains in social mobility from the degree. In the end they were actually *worse* off than had they not attended university. This is disgusting. The fact that the UK is following in this trend should be worrying for everyone.

The answer to poor access should not be expanding the debt burden for students of colour or from marginalised backgrounds. It should be aggressive outreach and funding FOR ALL. A 2016 study found that 2.4% of white students had started a PhD within five years of graduating, compared with just 1.3% of black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) students. A key factor is the financial barrier: only 1.2% of PhD studentships from UK Research and Innovation research councils have been awarded to black or black-mixed students in the past three years. If we care about diversity and ensuring that higher education is kept alive with fresh perspectives from voices traditionally excluded then we should *fund* those students.

Without funding you either lock people into unsupportable debt burdens that will seriously ruin the future they’re furiously working for, or you guarantee that Phds are only for the rich.

Some of this is the fault of universities. Some of this is the result of government policy. Some of this is the fact that universities are institutions that are part of the world (shaped by it and shaping of it) and thus can’t be expected to look all that different from anything else. But we can and should hope for better. Especially if a Phd can’t be expected to “pay off” in a tangible sense. For all the intangible benefits of doing a Phd to present themselves requires the space and time that funding provides. I am forever grateful for the opportunity I was given. I wish it were available for more people.

In the US, post-docs often end up earning less than Librarians and mail carriers

A New Yorker writer recently told me that if I want to make it as a writer I have to leave London. Fair advice except a) I’ve done that before and b) it’s my home? where my family is? and all my friends since childhood?

if only it were this easy. I fail at this everyday. It is a practice, I think, something that can only ever be worked towards. I often feel hollow/empty and frustrated with what I’m doing. More-often-than-not I sadly have no idea what my purpose is or why I continue. But as someone I love very dearly said to me recently. Ultimately when the doubts come we ask why? and we hear a quiet voice that says/ because. So we continue.

for obvious reasons, the centuries-gone thinkers of old are Straight White Men. In some cases, their sweeping generalisations of the world have caused untold violence and destruction for millions of people. There is a reason we don’t still think in this way.

especially true for people who do ethnographic work, where you are literally supposed to check your questions at the door and instead let the moral universe and local stakes of the people you are doing research with inform the questions you should be asking

Look, I think all higher education should be free. I don’t think we need multi-million pound investments in big-name architect designed buildings when you have one student committing suicide every four days in UK universities

This is different for US universities where Phds, for the most part, are funded (with some glaring exceptions). However, they are paid so badly that there have been protests on campuses in recent years to get $15/h, which would amount to barely the living wage in big cities. US Phds also last significantly longer (7 years minimum for my course if I was in America), have much more teaching/research assistant requirements and generally less freedom than the UK. In other words, sure they pay you, but they get their money’s worth out of you.

My funding body sent me to conferences in Vancouver and Shanghai. In Vancouver I met, amongst other people, professor Kuan at CUHK who has helped me shape my research in profound ways.